School Matters

Children across Latin America have big dreams but are facing big obstacles.

Around the world, children are travelling further, risking more, and overcoming greater obstacles for the chance to learn.

In Latin America alone, students cross floodwaters, walk unsafe roads, and study in classrooms at risk of collapse – just a snapshot of the wider pressures facing education globally.

These stories illustrate the urgency behind the Global Partnership for Education’s Case for Investment 2026–2030 to build resilient, inclusive learning environments that improve the future for generations to come.

On certain mornings, the river in northern Peru looks almost calm, brown, slow, and apparently harmless. That is when 14-year-old Stalin (above) rolls up his trousers and walks straight into it, feeling for the riverbed with his toes. He knows the route to school by heart; he also knows how abruptly the water can rise, and how the current can seize you.

“Sometimes people die after being pulled away by the current,” he says. And so, each year, when the rains fall harder and stay longer, Stalin stays at home, missing weeks of lessons, unable to keep pace with classmates who can cross dry land to get to school. “It’s frustrating,” he says. “I fall behind my classmates.”

Meanwhile, in another part of Peru, 16-year-old Yulitza (above) climbs onto an ageing motocicleta with her brother. The journey to school takes an hour and a half, longer when the bike breaks down, which it does several times a week. “Sometimes we find another way to get to school, but there are days when we just have to turn back,” she says.

“I didn’t want to go to the schools near my village,” Yulitza explains. “There are too few teachers. And even when they’re present, they often don’t teach. Sometimes they send the students home early, like at 1pm, while school is supposed to go until 3pm.”

Her decision to attend a better school comes at a cost: 30 soles a week for fuel, extra expenses for photocopies, and constant pressure from her father, who doubts the value of education. “He often says we should just be sent to work instead of being allowed to study.” Despite it all, her ambition persists: “I want to be so many things, maybe a psychologist, a doctor, a teacher, or maybe an accountant.”

Across the Andes mountain range, in Bolivia, sisters Carla, 14, and Janet, 12, (pictured above) wake at dawn in a boarding school far from home, a place they did not choose but must attend because there are no secondary schools in their village; the journey is too long and too expensive to make each day.

After their mother died, Carla spent two years out of school, caring for the family while her father tried to earn enough to send her back. Now she and Janet study side by side, sharing beds, both struggling with homesickness. “Only kids from distant places come here,” Carla says. “I really miss my father and brother.”

Further south, in Tarija, single mother, Dalita, 37, (above, with her children), wakes before sunrise to open her shop. She is, as she puts it, a mother and father to her children, working from six in the morning until eight at night, trying to save enough to buy schoolbooks, notebooks, and the uniforms that mark a child as eligible to enter the classroom.

Her bills stack up on the table, alongside the fear that one day there will simply be no more to stretch. And yet she stays the course. “I’m not the kind of mum who gives up,” she insists. “I would sacrifice anything for them, just to make sure they can stay in school.”

Also in Bolivia, six-year-old Gael (above), who once relied on a wheelchair, walks a little now, carefully, proudly. But inside his school, the absence of ramps and accessible toilets turns every day into an obstacle course.

“I wish there were ramps,” he says. “I can’t go to the toilet by myself.” His teachers have not been trained in disability inclusion; the building was never designed with children like Gael in mind. His determination fills the gaps left by systems that have not yet adapted to him.

In Colombia’s Chocó region, 13-year-old Katarina (above) studies in a building she knows could collapse. “The cracks in the wall get bigger when it rains,” she says. “One of the walls collapsed down the hill.”

Water drips through the roof; electricity fails; students wait in dim classrooms unable to access the internet. “Learning without internet just doesn’t make sense,” she says.

On a warm afternoon in another part of Peru, 12-year-old Alicia (above) sits in a quiet corner of her all-girls secondary school, pencil in hand, slowly working through multiplication tables she never properly learned. The gap between primary and secondary education is wide where she lives, a fault line thousands of girls fall through each year, but Alicia is determined not to be one of them.

“The classes in primary school were different, particularly in maths. I didn’t know how to multiply or divide, or even about odd numbers,” she says. Her sister, now studying at a national university, helps her each evening with homework. “I want to go to university just like her.”

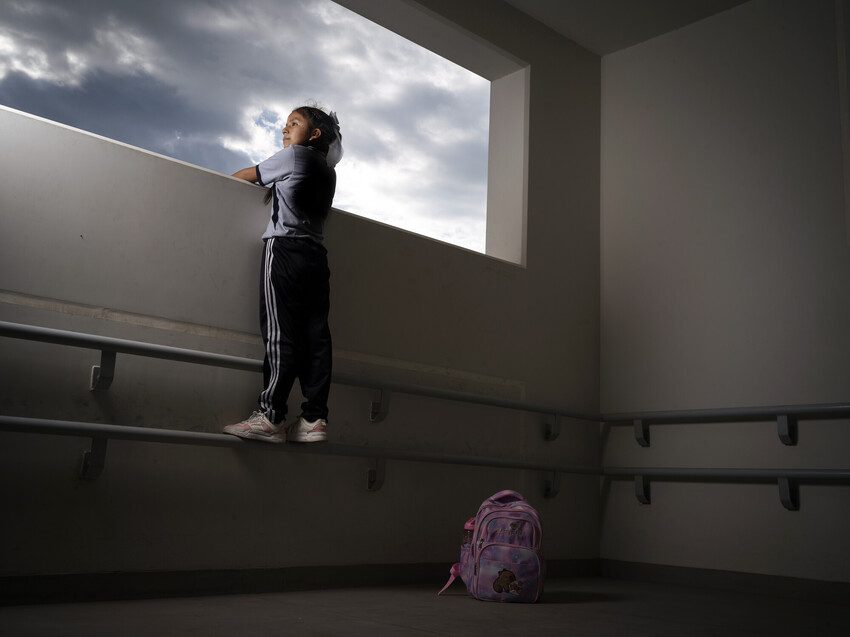

For 12-year-old Erika (above), the walk to school comes with a specific fear. “A motorcycle followed me,” she recalls. “The driver cut me off and tried to grab me. It was really scary.”

In Ecuador, sexual violence in and around schools is widespread, and her father worries constantly, not only about harassment but about the absence of essential sexual education.

“Schools here are afraid to teach children about their bodies and consent,” he says. “It would prevent many teenage pregnancies.” Erika wants to study; her parents want her safe. The two wishes shouldn’t have to cancel each other out.

Education under unprecedented strain

These children’s daily struggles reflect a global picture: education systems around the world are under unprecedented strain. Today, more than 270 million children and young people are out of school, and education faces a US$97 billion annual funding gap.

When systems weaken, girls face the steepest consequences, including heightened risks of child marriage, early pregnancy, and gender-based violence, all issues that derail futures before they can begin. And yet, we know that education is one of the most powerful investments a society can make.

Education can improve every development goal, from health and jobs to peace and stability. Education is not just a service, it is a lifeline, a stabilising force in a world of climate shocks, economic strain, and uncertainty.

Taken together, these children’s stories form a pattern repeating across regions and continents. The world is changing faster than education systems can adapt. Climate shocks are washing away bridges, closing roads, flooding classrooms. Rising costs are pushing families to choose between food and schoolbooks. Distance and isolation keep children – especially girls – out of the classroom. Exclusion continues for children with disabilities.

The case for investment

The Global Partnership for Education’s Case for Investment 2026–2030 argues that unless the world acts now, these pressures will turn today’s inequalities into tomorrow’s crises. Education systems must be shock-responsive, inclusive, designed for girls, and resilient by design, not merely patched together after disaster strikes.

The children above are already living in the future described by the Case for Investment. Their daily journeys reveal what is at stake: not just whether a child reaches a classroom, but whether that child can keep pace with a world remade by climate, conflict, and inequality.

Resilience is not an abstract concept, but built child by child, school by school, through long-term, predictable, equitable funding.

Across the Andean region, the Safe Horizons project, funded by ECHO and implemented by Plan International, offers a glimpse of what resilience can look like when investment reaches the right places. For Stalin, this means extra tuition and disaster-preparedness training. For Carla and Janet, a chance to stay in school despite financial strain. All these children’s stories illustrate a truth at the heart of the GPE investment case: resilience is not an abstract concept, but built child by child, school by school, through long-term, predictable, equitable funding.

The Case for Investment calls for global leadership and sustainable finance to create an education system strong enough to carry millions of children towards the lives they want. Investing in GPE today is an investment in peace, equality, and long-term prosperity, ensuring that every child, especially every girl, can learn, thrive, and lead change for their communities.