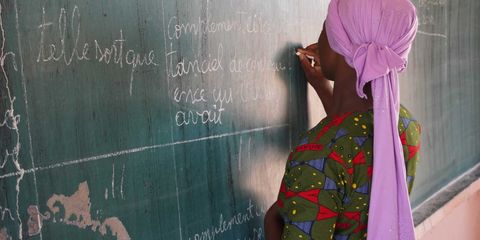

Coulibaly, 25, is among a number of young activists in Mali leading the movement to end female genital mutilation.

“You were born yesterday, and you are the one who wants to talk to us about female genital mutilation? This is what parents say when we try to talk to them about it,” says 25 year old Coulibaly, a youth activist working with Plan International to end the practice of FGM in his community in Mali.

In a country where more than 85% of women and girls believe FGM should continue, ending FGM is not an easy task. In Malian society, a woman who is not cut is often considered to be unclean. She may find it difficult to marry and be socially excluded. Many also believe it is a requirement of Islam.

FGM considered taboo

“Our challenges remain high in a society where girls do not have a say when it comes to female genital mutilation.”

Coulibaly

The subject of FGM is considered taboo, so those who are most affected do not discuss it or the physical or psychological consequences. Transforming the situation is challenging as the practice is deeply rooted in cultural and social norms.

“Before, when we talked about abandoning female genital mutilation, we were banned from the village,” explains Kouradjei, 60, who is a former FGM exciser. “I gave up the knife a long time ago. During my career, I have seen some awful things. I now know the consequences of the practice of female genital mutilation and I am convinced that it has no advantages for women.”

Mali is one of the last remaining African countries without national legislation banning FGM. It is estimated that 9 out of 10 girls and women in Mali have undergone FGM, with the highest rates occurring in the south.

Nationwide work against harmful practices

Plan International has implemented projects in 180 villages in 5 regions of Mali with the aim of eradicating FGM. The communities we work with are at the heart of our interventions, so we establish village committees to create action plans to tackle the issue.

By setting up key partnerships with government agencies, local authorities, children’s organisations and youth groups we have seen a fall in the number of cases of FGM in the communities we work with, however we still have a long way to go.

“Our challenges remain high in a society where girls do not have a say when it comes to female genital mutilation, a society where young people are not consulted when it comes to our rights. The fight is hard but noble,” Coulibaly says.

Tide turning against FGM

Of the 180 villages we work with, 92 have now declared themselves to be FGM-free. In one of these villages in south-western Mali, the village chief explains why: “In our village, men, women and children are now aware of the consequences of FGM. Our excisers are being converted into activists for the abandonment of the practice. Our daughters are no longer excised. We have abandoned the practice of female genital mutilation.”

But it is Mali’s young people, the future generations, who will prove the most effective in ensuring long term change in the country.

“We are now able to convince adults and our peers of the consequences of FGM,” Coulibaly explains. “Our parents are lining up alongside us from now on to fight against FGM. We remain more committed than ever to ensure that no more girls suffer the consequences of this practice.”